Jeez, it’s hard to believe that yesterday was the one-year anniversary of my defending my PhD thesis… mostly because the COVID pandemic has made it seem like it was so much further in the past. Time has lost all meaning, I know. I figure that this makes today as good a time as any to write about how the whole process went. (For those who are curious enough to actually read the damn thing, you can find it here. Be warned, though – dissertations are lengthy and dry reads in general, and thanks to my tendency for overly detailed writing, mine is apparently the longest one in NPSIA PhD history. If you’re not really interested in nuclear deterrence, there’s a non-zero chance of slipping into a nap and/or coma. Keep a couple of cups of coffee on hand.)

I have a couple of reasons in mind for writing about this. For one, the whole process felt like such an ordeal that I tried to not think about it for most of 2021. I figure that writing this post will be a form of catharsis after feeling… well, pretty burnt out about academia, really. Another reason is that it might give current and prospective PhD students an idea of what they might face. I can’t speak to how other departments handle things, but I felt that in my department, PhD students had very little formal guidance in what to expect when defending their thesis, much less how to prepare for it. The expectation seemed to be that a) you would attend defences on your own time to get an idea of how they go, b) you’d consult your supervisor on what to do, and/or c) you’d figure things out yourself. Admittedly a) is mostly reasonable, except that PhD defences are a rarity – having 3 in a year would be unusually high – meaning that there are limited opportunities, and… well, there had been a rule change for a brief period in the pandemic that would make that somewhat challenging. Writing about my own experience with the defence process will hopefully help with this issue, at least a little bit. At the very least, I’m hoping that it makes it clear that the defence isn’t a formality, and maybe some of the things that can go… well, maybe not wrong, but pretty awry.

(In the interests of not stirring up trouble, I’ve elected to remove the actual names of individuals involved in the story, and instead refer to them exclusively by their titles.)

So, without further ado…

The Submission

This was probably the most straightforward part of the process, although it had its share of confusion. This meant 1) getting the approval of my dissertation committee (supervisor + two advisors), 2) informing my department of my intent to submit a draft for defending (and approximately when), 3) submitting a checklist indicating that all the dissertation rules have been followed, 4) making sure that my supervisor submitted the authorization form with possible external examiners, and 5) actually submitting the dissertation. This unsurprisingly takes a while: I started checking with my committee as to whether my thesis was ready to defend in late July 2020, got the OK from all three around late September (after making further tweaks), and actually submitted it online in in mid-October. Plus, after all that, the defence date was set for December 4 – a full two months later!

Why is this? Well, Carleton requires the dissertation to be submitted to the supervisor at least 6 weeks before a possible defence, and uploaded at least 4 weeks before. This is partially because the date has to work for everyone involved: the student, the committee members, the chair, and the internal and external examiners (the former being from another department in the university, the other being based at another university entirely). Selecting the external examiner is also a big hurdle, because the department has to contact possible examiners one at a time, then give them about a week to respond before moving on to the next one, then making sure they have the time to actually read the dissertation in detail. (I know someone who ended up having to wait 6 months to defend his dissertation because of difficulty in finding an examiner). Also, the PhD candidate doesn’t get to pick the examiner – that’s the supervisor’s decision. Sure, the supervisor can consult the student on possible examiners, but they don’t have to listen if they do.

So, I finally found out that December 4 was the earliest possible date for my defence around mid-October, shortly before uploading the defence version of my dissertation (which meant no more edits until after the defence). I received the proper notice for the defence around the end of October, which confirmed the date and let me know who the internal and external examiners would be. The former wasn’t a problem – this was a professor from the Political Science department who was an expert on Israel, and therefore made perfect sense – but the latter was… confusing. Specifically, the external examiner was not only not on the list of about a dozen names I gave my supervisor, but I had outright never heard of before. Looking at his list of publications didn’t clarify things much either, since it didn’t really seem to relate to anything I was doing in the dissertation. I still haven’t found out why my supervisor chose this external (because there’s no other way for his name to have ended up on the list); I can only assume that he saw one reference to nuclear weapons in an article he wrote on ballistic defence and thought it was close enough. At the time, I thought that this wouldn’t be an issue, but this turned out to be… incorrect.

The Preparation

Preparing for the defence proved to something of a pain, primarily because the actual requirements for the presentation seemingly aren’t written down anywhere. I ended up having to consult some PhD alumni about their own experiences, as well as searching on Google to find the Carleton regulations on the defence format (linked here again!). To make a long story short, I would have to find a way to boil down the main points of the dissertation into a 20-minute presentation (possibly even shorter). This was somewhat tricky considering it ended up being around 400 pages long – admittedly in part because a dissertation involves a ton of repetition, but also because I tend to be overly wordy (in case this blog post didn’t give that away). I started working on the presentation over a month before the defence, and went through a few rounds of revising it to try and cut it down to a manageable length. By late November, it seemed like I would be ready for the defence.

The “Unpleasant surprise”

And so, with just 10 days to go before the defence, I received an email from my supervisor with some incredibly worrying news. As it turns out, every external examiner has to write a report on the dissertation they’re examining to confirm if they think it’s ready to proceed or not, then submit it to the Dean of Graduate Studies. Normally, the student never sees this report, unless the examiner thinks that the dissertation isn’t ready to defend… which turned out to be the case here. The report seemed to be very mixed: on the one hand, the examiner thought the dissertation was well-researched, but on the other, he thought that it didn’t actually support my argument and had methodological issues. Some of the critiques were admittedly fair, while others made no sense and seemed to boil down to “well, that’s not how I would have done it” (e.g. his complaint about my not using China as a case or his insistence that I should refer to a particular author’s definition of general deterrence). It also seemed very strange for him the dissertation for being structured “in social science terms” when it’s written in a field of… social science (last I checked, international affairs wasn’t exactly a hard science on par with physics). The problem here was that I simply couldn’t ignore the external’s critique and ride on the rest of the examiners passing me: as it turns out, the university rules explicitly state that the majority decision has to include the external, essentially giving them veto power.

In any case, I was faced with 2 options at this point. I could either go ahead with the defence and just do everything I could to pre-emptively address all the issues raised (which would essentially mean re-working what I had up to that point), with the risk of potentially failing the defence (which would mean having to redo it) or even the dissertation entirely, which is outright Game Over – you’re gone from the program for good. The other option was to withdraw from the defence, revise the dissertation, and try again later on with a different external. This would not only would drag out the PhD even further, but ran the risk of having an external come up with a whole set of critiques again. I ended up opting for the first option, which seemed better, but proved to be… stressful. (By which I mean that going by the resting heart rate data from my Apple Watch, I seemed to be having a constant panic attack until the weekend after the defence.)

With all this in mind, I set to work essentially scrapping the earlier version of the defence presentation and starting from scratch. I was somewhat lucky in having managers at work who were OK with me taking that entire time off (as unpaid leave, since I was still on a casual contract that didn’t allow for paid vacation at the time), so I would be able to work on the defence revisions during the day instead of having to do everything at night. I was also able to get suggestions on how to proceed from my committee members (who also all seemed to be blind-sided by the critique and felt that I was essentially being judged on a wholly different set of standards), which helped speed things up. It still ended up coming down to the wire, though, as I kept tweaking the presentation and my responses to potential questions until the night before. I also ended up only being able to do a single practice run with an audience (also the night before). Fortunately, the friends who acted as my audience over Zoom were incredibly helpful, giving a ton of feedback on every aspect of the presentation (down to pointing out how I should change the font size) over the course of… 3 or so hours, if I remember right?

It’s worth noting that on top of all this, Carleton decided relatively late in the process to prohibit guests for dissertation defences taking place on Zoom. Normally, PhD students are allowed to invite people to attend a defence, and professors and other students can also attend to observe (and the former can even ask their own questions during the Q&A). Now, however, the university decided to ban this, and never really provided an explanation or even much in the way of warning. This meant that they had seemingly arbitrarily decided that, for the duration of the pandemic, PhD candidates wouldn’t have friends and family acting as silent support in the audience and that other PhD students couldn’t observe a defence themselves. The second point was especially egregious since, as I mentioned before, attending a defence is one of the only ways to find out how it works. I don’t think anyone was happy about this – NPSIA professors were reportedly infuriated at the change, and every student I talked to (in and out of the department) reacted even more negatively. The professors apparently managed to push back enough to be able to attend my defence, and I suppose the wider backlash to the practice ended up being vocal enough that by the following summer students were allowed to attend again. To this day, I don’t have a straight answer why this was implemented (my guess is to have less for the chair to do), but it proved to be another unnecessary source of stress.

Judgement Day

Finally, it was the big day. The defence was only taking place at 2:30 PM, so I used most of the morning to keep preparing. This meant going over my prepared answers more to avoid just reading off answers, continuing to tweak my presentation notes to avoid rambling too much, and making sure that I remembered key details of my cases correctly. (It wouldn’t exactly make a good impression to forget when the Six-Day War took place or who fought in it!) By the time the defence started, I had multiple piles of paper in front of me, ranging from presentation notes and my responses to the external’s critiques to a pile of cue cards that I scribbled important dates and names on just to make sure that I had them handy. As it turns out, writing all those notes worked better than I expected, because I somehow avoided referencing them at all (probably because the constant writing and rewriting led to my memorizing everything).

It’s probably important for me to explain just how the PhD defence is actually structured before I go into details about how mine went. Ironically, the defending student doesn’t participate in the initial part, which is a closed meeting between the committee, the examiners, and the faculty-appointed chair to determine if the defence should go ahead at all. If they agree to that, the student gets invited back in and the chair explains the procedures. It’s only at this point (maybe 15-20 minutes after the official start time) that the student gets to give their “introductory statement” – namely the 20 minute presentation giving an overview of their work, usually with a PowerPoint. After that, there’s two rounds of Q&A by the examination board for about 45 minutes or so each, with professors in the audience getting to ask their own questions in the second round. After all that, the student gets to make a closing statement and then gets booted out of the room while the examination board deliberates. Altogether, the actual defence can take up to 3 hours, and the examination board deliberations on whether the student passes and what the final “grade” is can go on for an hour on top of that.

The presentation portion of my defence went fairly smoothly, considering that I’d only managed to practice going over it once. The Q&A proved to be the trickier part. The questions from my committee members and from the internal examiner were largely as expected, so I was well-prepared for those. There were some critiques and suggestions that I hadn’t really expected, but these were fairly straightforward or occasionally went beyond the scope of what I was researching (and for those getting ready for a defence, it’s better to acknowledge this than try to improvise an answer).

What was tough was the questioning from the external examiner, which seemed to be equally divided between critique that made sense, having a wholly different perspective from the dissertation, and at some points seemingly not having bothered to read some parts. To begin with, he outright stated that he hadn’t bothered reading the introduction chapter in response to my explaining that the answer to one of his questions, which still strikes me as unusual. He also didn’t understand the process tracing methodology I used and said that it wasn’t a thing when he was a PhD student, which was odd when a) he could have simply looked at Wikipedia for a brief explanation and b) it’s discussed in the major qualitative methodology books, so I don’t know how he missed that over several decades. I’m pretty sure I also managed to get on his bad side a bit as well when I critiqued realism in favour of constructivism in one of my answers (by saying that it’s good for system-level analysis but not so much for individual state behaviour). Also, it seemed very strange that I had to explain why Israeli nuclear deterrence wouldn’t work against Palestinian terrorism (hint: it’s wholly disproportionate to the point of absurdity, plus nuking the territory next to your small country is going to cause problems). Overall, it became increasingly clear that the external examiner was the only one who had significant issues with the dissertation, and a lot of those seemed to boil down to “this isn’t the paper I would write, though.”

Altogether, the defence lasted for just about the allowable three hours, and the deliberations took almost another hour on top of that. As you can imagine, this was pretty stressful, especially since the early December date meant that it was already pitch-black outside. It came as a huge relief that the decision was that my dissertation passed with major revisions (as in the required changes are significant enough to need approval before final submission, not that the rewrites are massive). I didn’t necessarily agree with the required changes, or the fact that I would need to work through the holidays to get them done in time, but I was happy to have just passed after all the stress of the preceding week. (It is worth noting that while I was supposed to be sent a list of the required changes by the Faculty of Graduate and Postgraduate Affairs, but for some reason I never did. This was less of an issue than you’d expect, since all the changes were those requested by the external, but still.)

The Aftermath

The first thing I did after the defence was… not touch anything related to the dissertation for several days, and instead went back to Montreal for a break with the family. (Hey, I may have had a late January deadline of submitting the final approved version, but I still needed a breather.) After that, I had to go over the precise changes demanded by the external examiner with him. This was more complicated than you’d think, because the list he emailed me after the defence was… substantially more demanding than what was seemingly agreed to before – as in, requiring “re-drafting” of the literature review and methodology chapters instead of the additions to the former and the minor corrections to the latter. It doesn’t help that for whatever reason, the email failed to include any of the other committee members (or the Associate Dean of Graduate Studies who had somehow gotten involved at some point), which gave the impression of his trying to go behind everyone’s backs in pushing more work on me. I ended up having to push back on this in my response, and made sure that everyone else was CC’ed (and continued to do so in further email correspondence just to make sure it didn’t happen again). This seems to have worked, since the changes discussed in our Zoom meeting proved to be much more minor, to the point that it feels like the decision should have been minor revisions.

In any case, I ended up working on the revisions over a few weeks and sent them out to all the committee members for approval. Since past experience made it clear that it could take a few weeks for them to read through the whole thing (which I didn’t have), I made things simpler by highlighting every change I made AND creating a whole separate document indicating exactly where and what was changed. Altogether, I ended up adding around 15 more pages to the dissertation, mostly in the literature review chapter. It paid off, though, since the revised version was approved with no further requests for changes, letting me submit the final dissertation with plenty of time to spare (re: 10 days).

Lessons Learned

- Make sure that everyone on your committee approves of the dissertation before you apply to defend, not only because this may mean you’ve failed to address some horrible mistake(s), but also to make sure they’re on your side during the defence. (Sometimes this isn’t enough to prevent someone from publicly throwing you under the bus without warning, but not everything is going to be under your control.)

- Check exactly who your supervisor is putting down on that list of potential external examiners – you don’t want to get a nasty surprise down the line! Giving them plenty of options to choose from helps.

- Prepare, prepare, prepare: despite what people may claim, you shouldn’t treat the defence as a formality – there’s a reason you can pass the dissertation but fail the defence! If you don’t put in the time to prepare, you may find yourself having to do the whole thing over again in another 6 months (and the one time is already stressful enough!). Spend lots of time getting your slides done, writing up notes, and practicing in front of others, ideally fellow PhD students who can tell you exactly what needs to be fixed. You should aim to keep the impression that you’re just reading off sheets of paper to a minimum (because chances are you’re being graded on that. Yes, I know, you didn’t sign up for this to be judged on your public speaking skills.) Plus, you want to make sure you have answers on hand for at least some of the questions you’re going to be asked. On the other hand…

- Be ready to say that you don’t have an answer to a question or that it’s beyond the scope of your research. The examiners are all professors: they’ll generally be able to spot when you’re trying to bullshit your way through an answer and won’t be happy about it. Being honest about not knowing an answer or not having looked into a given topic (whether because you didn’t have time or just hadn’t thought of it) will show that you’re aware of the limitations of your research. Just don’t do this too much, or they’ll wonder if you actually know anything.

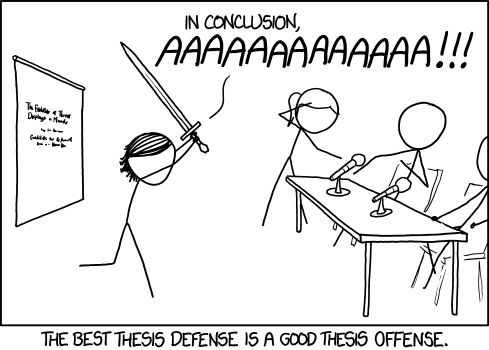

- If you’re doing your defence remotely (and if you’re reading this during the COVID-19 pandemic, you will), take advantage of this by making sure you’re as comfortable as possible during the defence. Yes, it’s going to be a weirdly impersonal experience like any other long video call, but you’re at home instead of a cramped classroom or meeting room, so you may as well do this in a comfy chair at your desk with a healthy supply of water on hand. (And you definitely want the water, because you WILL get thirsty from all that talking.) Maybe even put some encouraging decor in front of your desk for that extra bit of motivation! (There truly is an XKCD strip for every occasion.)

- Don’t be afraid to calmly push back on unwarranted critique. You’re a PhD candidate and the expert on your subject, not an unquestioning lump. Yes, if the critique is fair and valid, you should accept it. But if you know that it’s incorrect and you have the evidence to show that, make that clear in a polite response to the examiner in question. (Nobody will like it if you lose your temper, even if you’re right.)

- This extends to the post-defence revisions (if there are any): don’t let yourself get pushed into changing more than necessary: your job is to make the required changes, get any required approval, and submit the dissertation, no more. If someone wants you to change your work into something they would have written, they can go write their own paper/book instead of hijacking your work.

- Go celebrate once you’ve passed! Sure, you have the revisions waiting for you, but you’ve also survived what feels like a multi-hour interrogation and shown whatever impostor syndrome you have that it’s totally unjustified (in relation to your research and writing skills, anyways – no comment on other issues). Get a drink with friends, have a nice dinner with family, go read that 1,200 page fantasy novel sitting on your e-reader, whatever floats your boat! Plus, chances are that you’re in no state to actually start working immediately anyways – better to take the time to recover first.